Airflow, dynamic and static pressure

Fan marketing materials could not do without the use (or is it misuse?) of key variables. There are plenty of them everywhere, but no one anywhere explains the nature of how they work, always just the supposed consequence. After all, for expected sales, companies need you to understand their presentations, which often contradict the laws of physics. But we will take a look at them, in all simplicity.

This fan has “high static pressure”, so it is suitable for radiator fins. Another one has “high airflow”, so it’s the optimal choice for a case, for system cooling. By making these claims, fan manufacturers have created a great segmentation and have successfully convinced people that they are buying “the right” fans for both case air circulation and cooler heatsinks. But the general perception is a bit distorted on this one.

To shed more light on the issue of fan airflow and static pressure, we have devised a three-part mini-series of articles. Starting from the very basics, through the measurement of the “cooling performance” of fans on radiators, we will end up at the analysis of P/Q curves. To begin with, however, it is essential to understand the meaning of the basic quantities with which we will be operating. We may be starting too lightly, which more experienced readers will hopefully forgive us for.

The goal is for all of us to understand everything accurately, even those who may not be interested in fans simply because of a lack of understanding of what it is we’re actually measuring and analyzing in those tests.

Airflow – the fundamental parameter of fans. It expresses the amount/volume of air pumped over a certain period of time. Most commonly used are cubic feet per minute (CFM) or cubic meters per hour. We at HWCooling uniformly use the latter unit (m3/h) as it is more common in our latitudes (Europe). In the case of airflow, there is nothing that requires any special understanding. The higher the air flow, the better. Of course, optimally at the lowest possible noise level. Fans that are quieter at the same airflow are considered to be more efficient.

But what kind of quantity is static pressure? At this level, the quantity is often misunderstood, and it is mainly for this reason that this series of articles has been written. Here it is pertinent to note that in addition to static pressure, there is also dynamic pressure. These are quite different quantities which both convey different information and are measured differently.

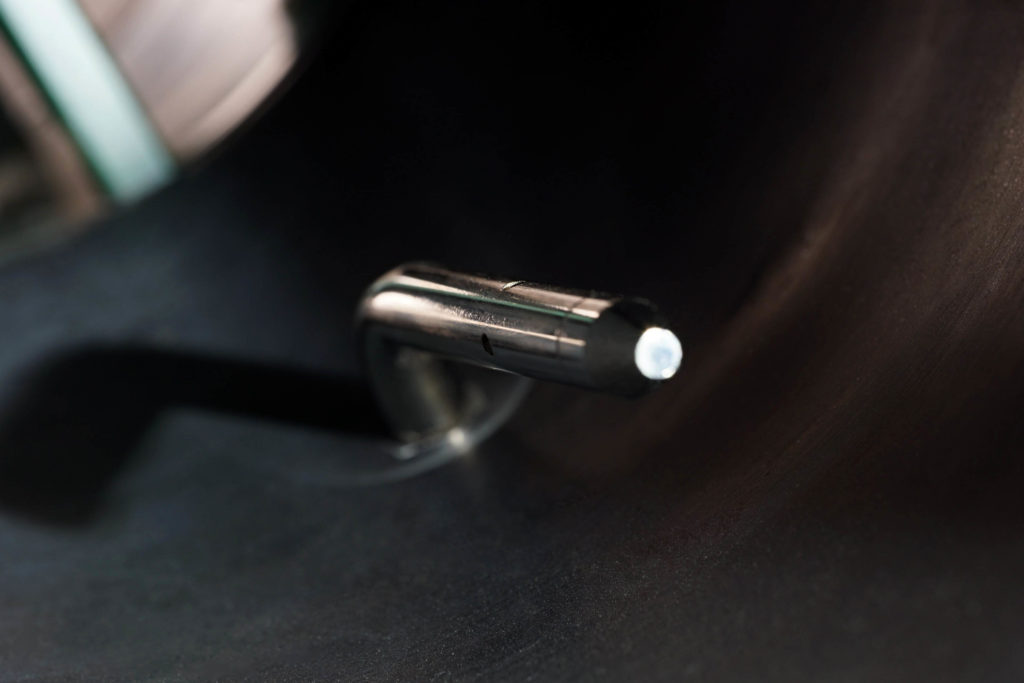

Based on the dynamic pressure, the air velocity (and consequently the airflow in cubic units as you know it from the fan parameters) can be calculated and the sensor of the measuring device is placed in the direction of the flow. In contrast, the probes for measuring static pressure are perpendicular to the flow axis. As you can see in the photo below. The sensor holes are on the sides of the probe (only the aerodynamic tip is frontal) and record “parallel” pressure. This indicator no longer speaks of the velocity of the airflow, but of the “force” exerted on the resistance of the environment in which the airflow is occurring. You can also substitute a case with a grille and a liquid cooler radiator for the environment.

The higher the static pressure is, the lower the loss of dynamic pressure or air flow. If two fans have the same airflow, but one of them has a higher static pressure, it means that it can better cope with an obstacle that then less restricts its basic parameter – airflow. Thus, in a more restrictive environment, such a fan (with higher static pressure) will be more effective.

And there is one more diametrical difference when it comes to measuring the dynamic and static pressure of fans. Static pressure is measured at zero airflow as opposed to dynamic pressure (no airflow limitations in measurements). This means that no air flows through the measuring system because the tunnel is properly sealed. To better understand the difference between dynamic and static pressure in the context of fans, a rubber balloon is often mentioned as a good example. When it is inflated, there is no dynamic pressure and only static pressure is exerted on its walls. The latter, by the way, is always the same in all directions.

Under the conditions described above, the highest static pressure can be measured. Of course, such a situation is not particularly compatible with practice, but when the tested fan achieves top-notch results under these conditions, it is no different, for example, even at 20 percent airflow with a typically highly restrictive obstacle. This will be covered in more detail in future articles in the series.

The intention of the pilot part was to give a brief, clear and factual introduction to the basic quantities that are dealt with in fans. The really attractive stuff is yet to come. Next time, we will discuss how we measure (and why we do so) the performance of radiator fans in tests and, finally, to what extent the popular P/Q curves expressing the relationship between airflow and static pressure are relevant. And most importantly, how the fan manufacturers have managed to pull a bit of a fast one on everyone for their own gain.

English translation and edit by Jozef Dudáš