That TPM 2.0 required by Windows 11? You might already have it without knowing. Today's processors have it integrated in BIOS/UEFI

Microsoft has unveiled Windows 11. In addition to new features and improvements, it also has higher HW requirements than Windows 10. It’s not performance that’s needed, but rather special features that not every PC may have. W11 requires TPM 2.0 (or Trusted Platform Module), which many people are now looking for. But there’s no need to get nervous, because in fact you probably already have it, just need to enable it. How to do it?

If you’re worried about the requirements of Windows 11, the first and general advice is to stay calm. It is not yet clear whether some requirements wouldn’t eventually be lowered, for example if Microsoft decided to apply them only to newly released computers and laptops, while users upgrading older computers, especially custom setups, would get much more lenient treatment. If you look at the lists of supported CPUs, they are very strict at the moment, they are even lacking the first generation Ryzen (and generation 2000 APU) or Intel Core 7th generation. At least on some of these processors, however, it could be possible to use an older CPU unofficially, or at least we hope it will end up like that.

TPM modules and TPM Headers

Anyway, now we’re just going to focus on the TPM 2.0 requirement, which seems to have triggered a minor panic, and people have started looking for TPM 2.0 modules in shops. There have even been cases of price increases and “scalpers” ramping up prices of TPM modules normally selling for a few dollars/euros enormously.

Thanks to Windows 11, people are scalping TPM2.0 modules as well now.

$24.90 ➡ $99.90 in just 12 hours pic.twitter.com/9TTHC2c47w

— Shen Ye (@shen) June 25, 2021

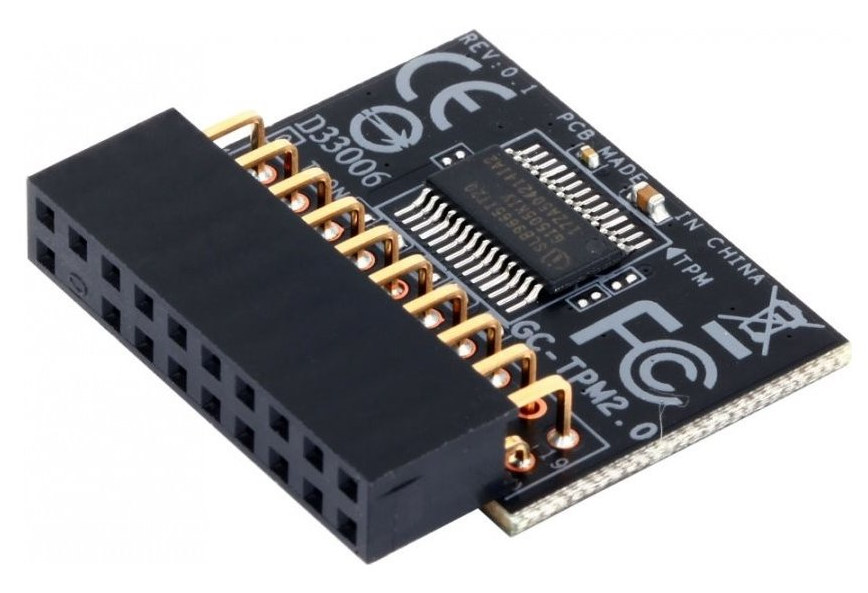

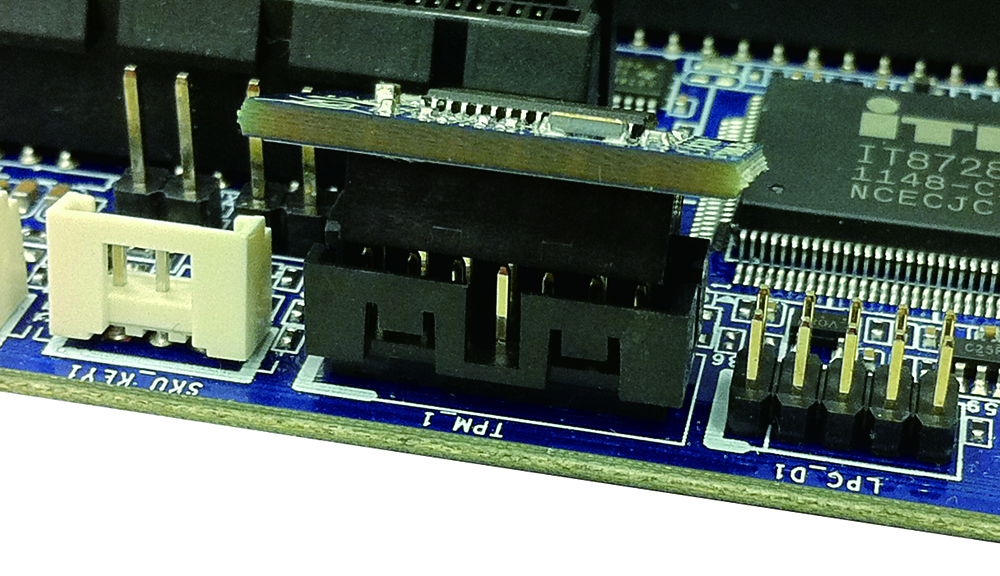

Trusted Platform Module is a small chip used to store encryption keys, certificates and similar sensitive pieces of data, it is used for Bitlocker encryption and it is possible that in Windows 11, more parts of the system will rely on it—which is probably why Microsoft would require it. The problem is that not every PC has it. Years ago, motherboards—unfortunately not all of them—used to have a special connector, into which a small module with a TPM chip was inserted. You can find it on the PCB or in the manual under “TPM Header”.

It is these modules that people have started to look for a lot and are wondering about their compatibility. But you better not buy them in a hurry. The problem is that the connectors differ from manufacturer to manufacturer. And the versions of the interfaces they use also differ. Older motherboards for Intel, for example, have TPMs connected via the LPC bus (as a Super I/O chip), but newer ones via the SPI bus—this will not be compatible and you might even damage something.

If you would like to connect this module to a motherboard with a vacant TPM header, you have to find out the exact type of module that is compatible with the board (from the manual or the manufacturer’s website) and purchase that particular type. Definitely do not try to buy a random module from one manufacturer if you have a board from another.

In fact, you probably don’t have to buy TPM 2.0. You have it in the firmware

But the fact is that if you have a recent processor or one just few years old, you probably don’t have to buy a TPM at all. For several years now, processors have been directly supporting the so-called fTPM (Firmware TPM) feature, which implements the functions of the TPM 2.0 module within the firmware of the motherboard and processor. No additional hardware is needed, you just have to find this option in the BIOS and turn it on. It’s usually not active by default, so your PC may look like it doesn’t have TPM 2.0 at first, but all you have to do is go to the firmware settings and turn on the option you need.

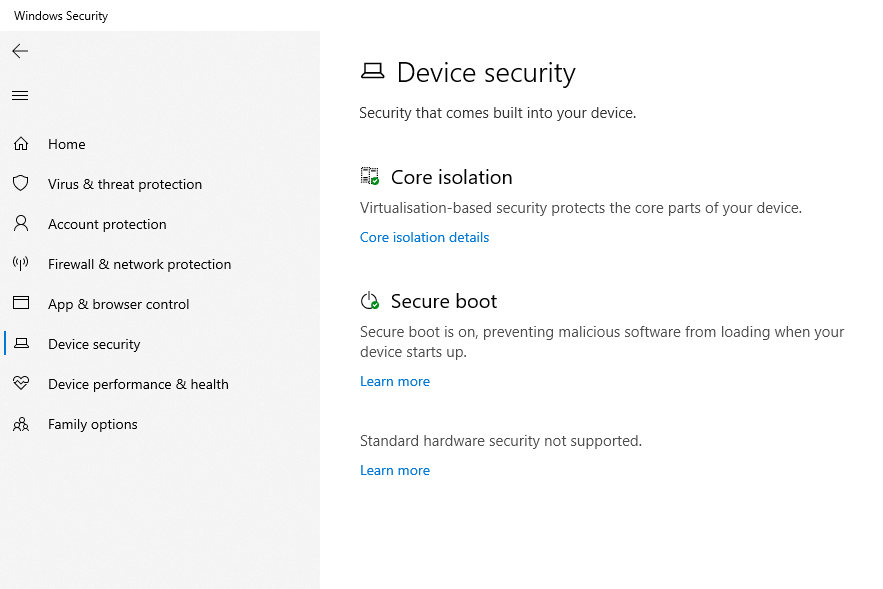

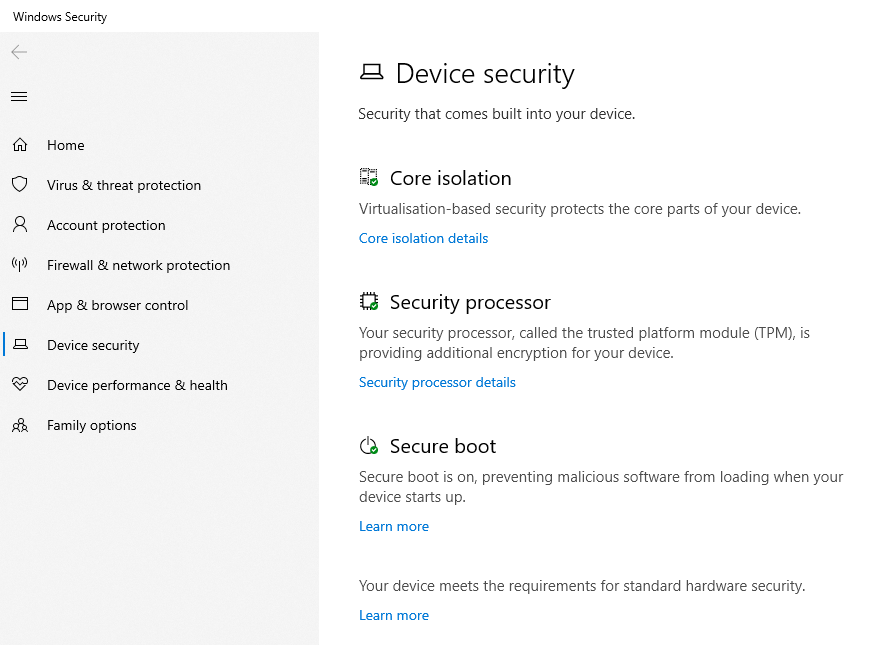

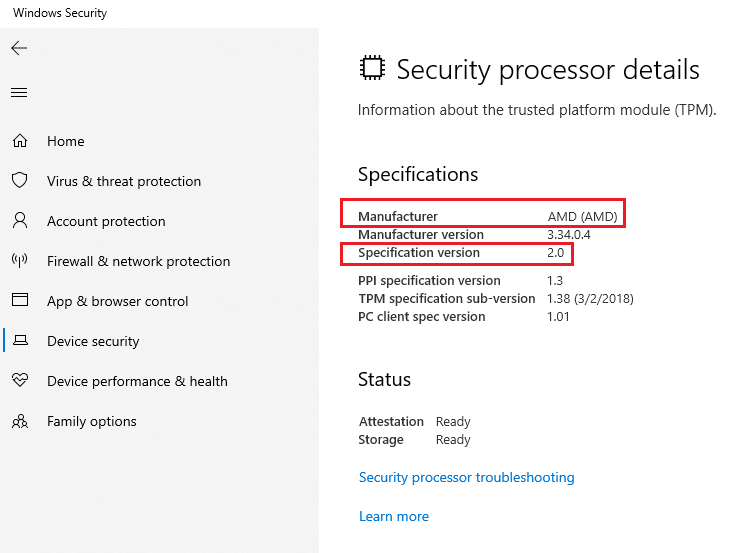

First, it’s good to see if you even have to bother with anything. Maybe you already have fTPM turned on, or you have an older OEM computer or laptop that has a fixed hardware TPM chip. Therefore, first verify that TPM 2.0 is present and turned on. Open Windows 10 Settings, “Update & security” section, select “Windows security”, then “Device security” and in the window that pops up, look for “Security Processor”, click on “Security processor details”. If this option is not visible, it means that you do not have TPM or it is not enabled.

On the other hands for those fortunate and TPM-endowed, it will look like this.

By entering that sub-menu, you can see the details of your TPM. If you are shown what I was and at the line “Specification version” it says “2.0”, then you’re all set, you already have TPM 2.0 – hardware or firmware.

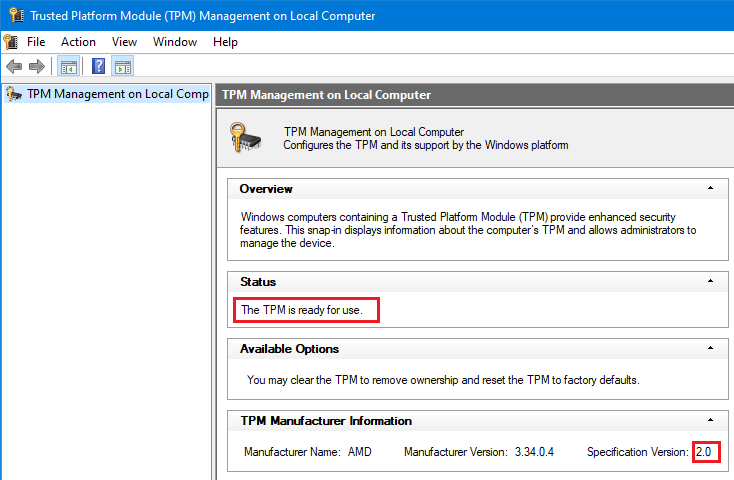

Another and faster method to get to this information is to press the Windows key and “R” at the same time, which opens a prompt to run a command. Type “tpm.msc” without the quotes and press enter to open the following window. Again, you can see the “Specification Version”, if 2.0, you’re lucky.

How to enable TPM 2.0 in BIOS (UEFI)

If you do not have the option active, you will have to go to the motherboard’s BIOS, more precisely to the settings of its UEFI firmware, because while today computers always use UEFI instead of BIOS, we just often still call it BIOS. See the motherboard’s manual or the Internet for instructions on how to access the UEFI settings, usually you do it by holding or repeatedly hitting a certain key (Del, F2, F10, etc.) while the computer is booting (not when waking up from sleep, you must restart). An alternative is to use an option from Windows (this is done via the “Advanced Startup” option you can find in Windows Settings).

Guide for AMD platforms

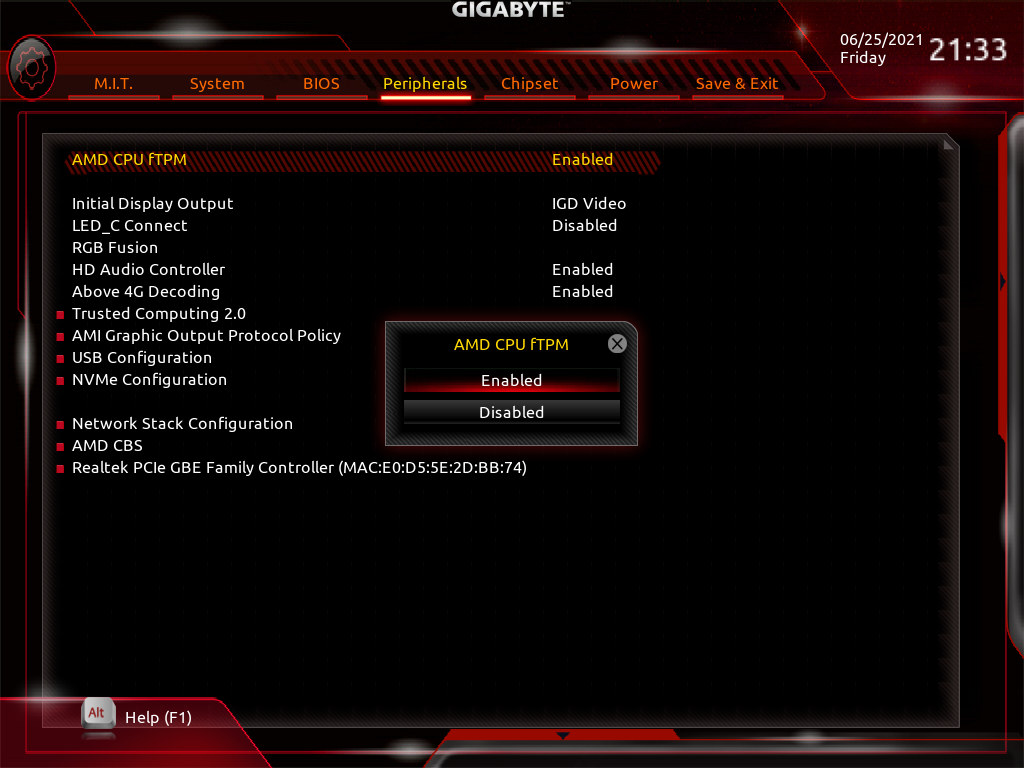

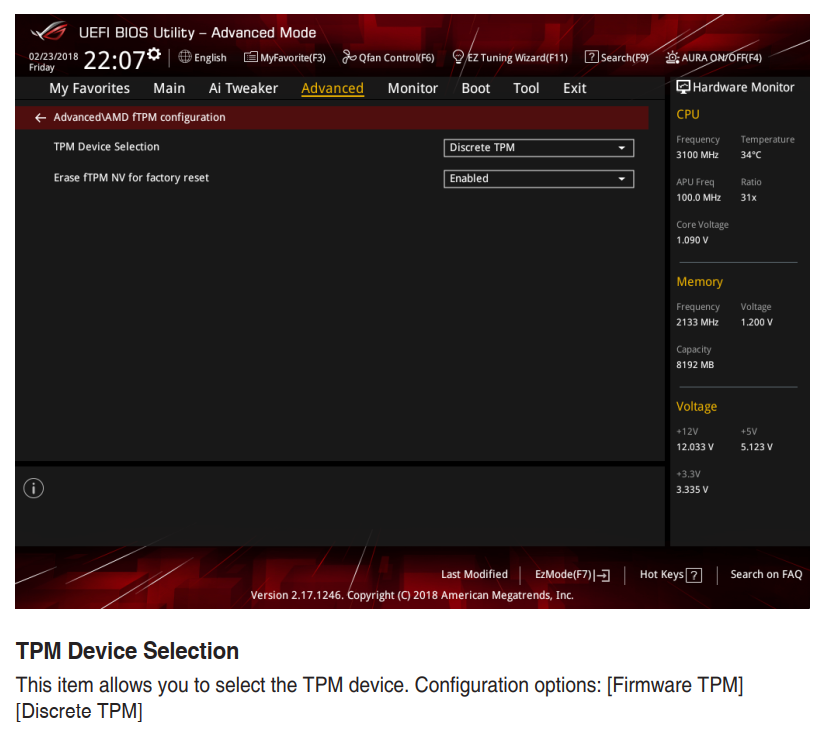

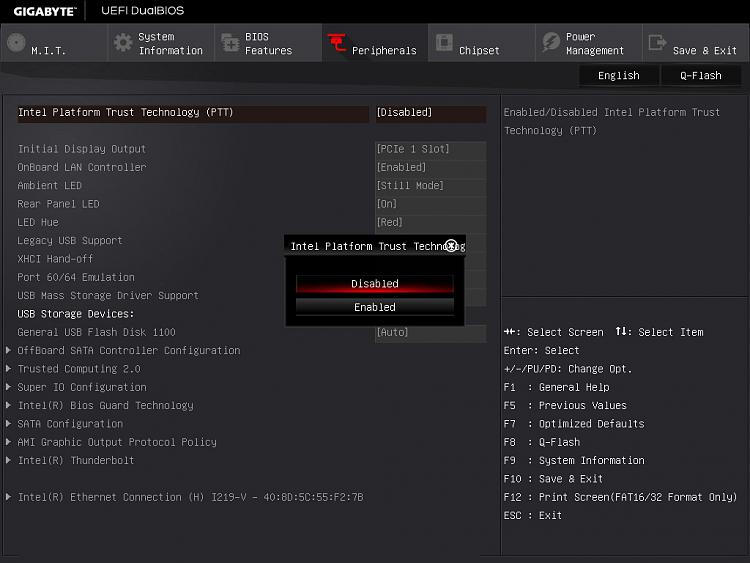

The option to turn on fTPM or Firmware TPM can be located in different places. For example, my Gigabyte motherboard has it in the “Peripherals” settings under “AMD CPU fTPM”. For Asus, the option seems to be in the “Advanced” and “AMD fTPM configuration” sections.

These options can either offer the option to enable or disable fTPM, but there can alternatively be an option of “Discrete TPM” and “Firmware TPM”. If you do not have a physical TPM, you naturally want to enable the Firmware TPM option.

Guide for Intel platforms

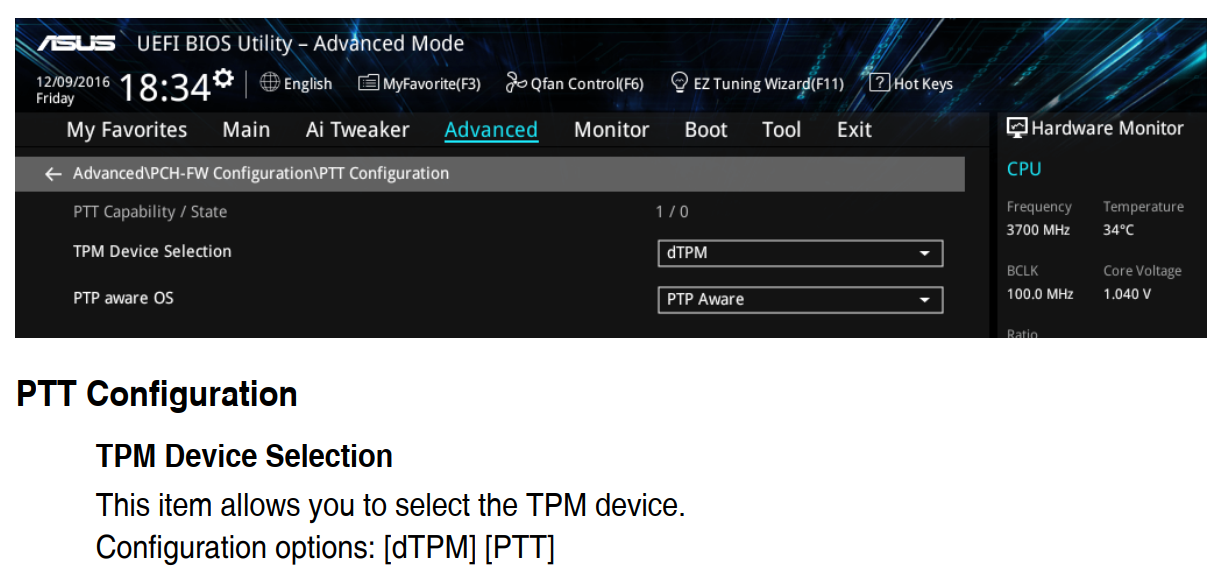

On Intel motherboards the feature is also sometimes referred to as “Firmware TPM”, but you may not be able to find an option under that name in the BIOS, as Intel renamed it to “Platform Trust Technology,” or PTT. Therefore, the option usually appears under this name in BIOSes, so look for PTT (or the long name – Platform Trust Technology). In the case of Intel, this function is not operated by the processor by the way, but instead by the chipset (same as Intel ME is), but that is just an implementation detail. However, for this reason, you will find the fTPM or PTT settings among the options for the chipset, under “Platform Controller Hub” or PCH Options/Settings, and so on.

For example, on Asus boards, this form of firmware TPM can be enabled in the “Advanced” section, then “PCH-FW Configuration” and there you should (hopefully) find the PTT option.

Some of you will probably be able to simply enable PTT, others may have to choose between “fPTT”, i.e. firmware PTT and “dPTT” or discrete PTT, which means a separate module. Selecting fPTT turns on the firmware TPM we want.

Options that turn on fTPM or (f)PTT can be labelled differently, so if you don’t find them right away, don’t despair. Try to google your motherboard model name and add “PTT” or “fTPM”. Alternatively, you can ask the manufacturer’s support for the location of this option in the BIOS, but searching the Internet will usually be faster.

Which processors allow you to enable TPM 2.0 in the BIOS (UEFI)?

Before you try the previous procedure, we should probably first discuss for which generations of processors and their platforms is this option available at all. You won’t have success with hardware that is too old. For example, the AMD FX processors and older APUs based on Piledriver, Steamroller and Excavator (various A6, A8, A10) did not yet have the fTPM feature.

The AMD platform should support firmware TPM 2.0 from the AM4 motherboards onwards, with Ryzen or Athlon processors based on a Zen architecture. It should be usable on A320/B350/X370 boards and newer.

Processors before Zen might actually require purchasing that hardware module and fitting it to the header on the motherboard—if you are lucky and there is one, that is.

It should be even better on the Intel platform. It seems that PTT (Platform Trust Technology) should already be supported by some Haswell processors or their chipsets (but sadly this only seem to be laptop models) and also modern out-of-order Atom SoCs, and Celerons and Pentium based on them, should support it since the 22nm Bay Trail chip (with Silvermont architecture) onwards. Therefore, even later low-end and energy-efficient SoCs should be able to provide PTT—on the condition that this option is provided by the board or laptop manufacturer to enable in UEFI. It is possible that sometimes the manufacturer has neglected to implement it and for that reason some of you will not have a chance to turn it on,unfortunately, even if the hardware is absolutely capable.

For desktop computers, the PTT option seems to be present in the Skylake processor generation and boards for them. The B150, Z170 and H110 chipsets all support this technology. So if you have a computer based on Skylake (Intel Core 6th generation) and newer, be sure to look for PTT, your board and its BIOS/UEFI could already offer this option.

Older computers with Haswell or Sandy Bridge/Ivy Bridge processors will again likely have to rely on a dedicated hardware TPM inserted in their TPM header (if present). However, again, I would opt to wait and see until the situation is clarified, in case it by a chance turns out that Windows 11 will run even without TPM. Or who knows, maybe you’ll in the end decide that you don’t even need Windows 11, at all.

Microsoft has confirmed that support for Windows 10 will be maintained all the way until 2025, so after the release of Windows 11, it will be possible to continue using the current operating system for a relatively long time without any need to upgrade to W11. All popular applications should continue to work on W10, so you’ll just have to reconcile with the harsh fact that your OS will have outdated looks and lack some new, but often not that vital elements.

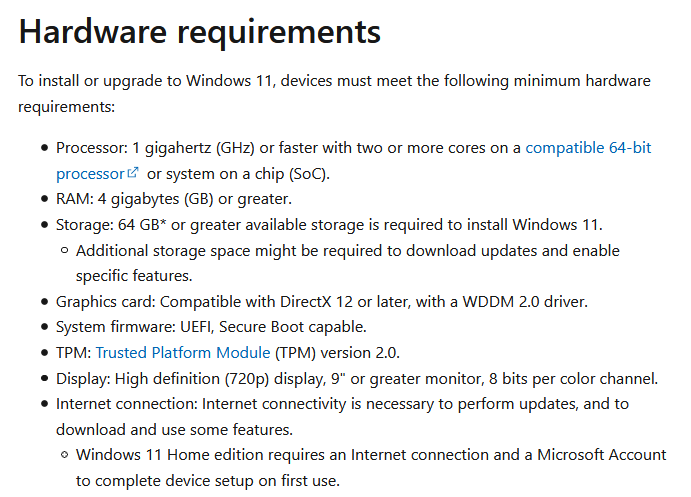

Also be aware that TPM is not the only problematic requirement of Windows 11. Microsoft also mentions a requirement for UEFI. So if you have a board with a standard BIOS, which could happen with a Phenom, AMD FX or Intel Core 2 processor, you fall outside the requirements for this reason already and it is useless to try to get a TPM. Graphics with DirectX 12 support and a WDDM 2.0 driver are also another item listed in the requirements. This means GeForce of at least the 400/500/600 (Fermi or later) generation, Radeon HD 7000 or later (GCN architecture—this means you need Kabini or Kaveri APU or later for integrated graphics), or Intel graphics from the generation of Skylake processors (Haswell iGPUs used to support DX12, but Intel removed the support because of a security vulnerability that it was exposing). If you do not meet this requirement, it again makes no sense to bother with TPM for now.

TPM 2.0 or just TPM 1.2?

Although most news and documents say that TPM 2.0 will be required, contradictory messages have appeared that even older TPM 1.2 devices might suffice. So again, we probably don’t need to freak out yet. There are many months left until the release of Windows 11, it is quite possible that some requirements will change. Therefore, it will be better to postpone any preparations done to your PC until all this clears up, because else you may worry a lot and later find it was all unnecessarily. Note that if you are building or buying a new PC now and choosing components and specifications, then that’s another story completely. In such case it is a good idea to se yourself up so that Microsoft’s current requirements for RAM size, UEFI Secure Boot support, DirectX 12 graphics and also TPM 2.0 (again, no need for hardware variant, the firmware TPM is all you need) are met.

Sources: Microsoft, TenForums, Asus, MSI, Heureka.cz, Gigabyte, our own

Translated, original text by:

Jan Olšan, editor for Cnews.cz